|

waLBerla 7.2

|

|

waLBerla 7.2

|

Game of Life in waLBerla

In this tutorial, we will implement Conway's Game of Life, the algorithm which made cellular automata popular. The Game of Life is usually formulated in two dimensions, meaning that the state of a cell depends on the state of its eight neighboring cells.

Due to this dependency on the state of the neighbor, we will need communication between different blocks. The neighboring cells can be located on different blocks and therefore possibly also on different processes. Hence, we start by introducing the waLBerla ghost layer scheme communication to solve this problem.

When implementing the algorithm itself, the stencil module is introduced, which provides a comfortable mechanism to access the local neighborhood of a cell.

Finally, we show how to load geometry information from files: For the Game of Life, there are some interesting starting patterns and it would be cumbersome to initialize these scenarios manually in the code. Instead, we can for example use png image files to describe the initial state of our cells.

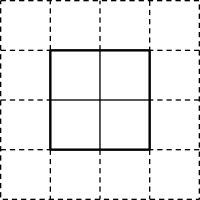

The lattice Boltzmann method or the Game of Life are algorithms based on cellular automata. They calculate the new value at a cell using the current value together with values from neighboring cells. When distributing the domain to multiple blocks, we can not directly access all neighboring cells of a cell at the border of a block, since some of them are in a different field::Field on a different block. Consequently, we need a mechanism to exchange data between these two fields. This will be done using ghost layer based communication: The field is extended by ghost layer(s), which are set to the values of the outermost inner layer(s) from the neighboring blocks. This is done before every time step of the algorithm, since the value in the outermost inner layer in the neighbor may have changed during the last time step. If we need values only from direct neighbors, one ghost layer is enough. In case we need to access a cell n steps away, n ghost layers are required.

For our algorithm, we need one ghost layer, so the first step is to extend the field by one cell in each direction. Instead of using the field::Field we switch to the derived class field::GhostLayerField. When we create a GhostLayerField, we have to specify the number of ghost layers, and the normal inner size of the field. The left ghost layer is located at coordinates (-1,y,z), and the right at (x_size_of_the_field,y,z). So the coordinates of the inner part of the field do not change!

Since one often wants to add GhostLayerFields to blocks, and the writing of an initialization function for every field would be cumbersome, there is a shortcut for this:

Keep the above code snippet in mind! This is the standard way of adding fields to your simulation.

So now we have the extra layer around our fields, but how can we keep them synchronized?

In order to setup the communication, we need two building blocks: First, a so-called "PackInfo" class is required responsible for packing and unpacking messages. For our specific application, we need a field::communication::PackInfo that assumes the given BlockDataID is a ghost layer field. It extracts the last valid slice of the field, and packs it into the message. It is also responsible for unpacking the message on the communication partner into the corresponding ghost layer. The second part of the communication infrastructure is a communication scheme. It controls the communication process, knows which processes have to communicate with each other, calls the PackInfos to pack messages, sends these messages over MPI, and performs - via the PackInfo on the other process - the unpacking of the message. The scheme that communicates with all direct neighbors is the blockforest::communication::UniformBufferedScheme.

So let us setup the communication for our GhostLayerField:

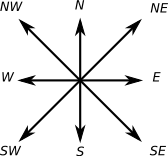

The UniformBufferedScheme takes as a template argument a stencil, which specifies which neighboring blocks communicate with each other. Since we are going to implement a 2D algorithm, we only need to communicate with blocks in x-direction (west, east) and y-direction (north, south), along with the corresponding diagonal directions (northwest, northeast, ...). No communication takes place in z-direction (top and bottom). Afterwards, a PackInfo is created with a fieldID as constructor argument knowing how to pack/unpack our field. The PackInfo does not know what type of field is stored for the given BlockDataID, hence, we have to pass the type of the field as template argument. It is possible to add multiple PackInfos to a scheme, which is usually done in case multiple fields have to be communicated at the same time. Here, only one message is sent to each neighbor per communication step. This message contains the data packed by all registered PackInfos. So instead of sending one message per field per neighbor, only one merged message is sent to each neighbor to reduce latency caused overhead.

The communication scheme class is a functor, so executing myCommScheme() starts the communication. In order to guarantee that the fields are synchronized before our sweep starts, we add the communication scheme functor as BeforeFunction to our sweep (which we still have to write):

In this section, the implementation of the Game Of Life sweep as a functor class is described. We start with the following skeleton:

This is basically the same as the SimpleSweep class from the second tutorial Register a Class as Sweep

Here, we operate on fields of type real_t. Usually, one would implement the Game Of Life with booleans. As we will see later, we use real_t fields due to nice initialization methods available for them ;).

The following Game Of Life rules have to be implemented ( taken from Wikipedia ):

For applying any of these rules, the number of alive neighbors has to be counted. We define cells to be alive if their value is greater than 0.5, otherwise they are dead.

In order to iterate all neighboring cells, we can use a mechanism provided by the stencil module. The stencil module defines an enum called Directions. Each direction encodes a certain coordinate offset. For example stencil::W (west) stands for the offset (1,0,0) whereas stencil::BSW (bottom-south-west) stands for the offset (1,-1,-1). Directions are described in detail here: Directions .

A stencil is a collection of directions. The D2Q9 stencil, for example, contains the direct neighbors in two dimensions including the diagonals and the center "direction" (i.e., the cell itself):

Each stencil provides an iterator to iterate all corresponding directions. Dereferencing this direction iterator yields a stencil::Direction. This direction can be used to access the neighbor of a current cell:

The neighbor function of the FieldIterator has been used to access the neighboring cell. This is always possible since we iterate only the inner portion of the field by calling field->begin() instead of field->beginWithGhostLayers(). Thus, we write only to the inner portion of the field but read one additional layer (the ghost layer). Because of the communication, the ghost layer is synchronized with the last inner layer of the neighboring block.

The above implementation still has a serious problem (bug!). When writing to cell (x,y,z), we read all the neighbor values. But, for example, the cell at (x-1,y,z) was already updated! Hence, we access the new value instead of the old one! In order to solve this problem, we make a copy of the field before starting the update algorithm and use this copy for reading and the actual field for writing:

Calling Field::clone() returns a pointer to a field that is newly allocated. We immediately catch this pointer with a shared_ptr. When the shared_ptr is destroyed at the end of the function, the dynamically allocated memory for the field is automatically freed and we don't have to take care of freeing the memory ourselves. Not freeing the memory would eventually cause the application to crash, since this algorithm is called many times and each time the memory usage of our application would grow.

As you can see, we now have to iterate two fields at the same time: field and copy. Iterating multiple fields at the same time is a pattern that occurs often, so there exist macros that take care of looping fields:

The WALBERLA_FOR_ALL_CELLS macro takes a list of names for the iterator variables and corresponding fields. Of course, iterating multiple fields only works if all fields we are iterating have the same size! This condition is enforced by the macro when run in debug mode. To use these macros the header field/iterators/IteratorMacros.h has to be included.

Additionally, if waLBerla is built with OpenMP support, this macro takes care of evenly distributing the work to multiple threads. Be aware: This only works without errors if every cell in the field can be updated independently, i.e., if the loop is easy to parallelize. If there are race conditions in your loop body, you cannot use WALBERLA_FOR_ALL_CELLS macros!

Using these iterators is a very convenient way of iterating fields. However, field iterators come with a runtime overhead. Thus, if you want better performance, you should stick to iterating fields using for loops for all dimensions:

First, we call Field::xyzSize() to get the size of the field. Calling this function returns a cell::CellInterval. This class is used to describe cell bounding boxes. By definition, the minimum as well as the maximum cell is included in the interval. After that, we loop all three space dimensions. Values in the fields are now accessed by calling Field::get() and Field::getNeighbor().

For iterating fields using x,y,z loops, there exist the WALBERLA_FOR_ALL_CELLS_XYZ macros. Of course, the macros for using x,y,z loops also include an even distribution of the work to all available threads if waLBerla is built with OpenMP support. The final version of our algorithm looks like as follows:

For many of the compute kernels included in the framework, waLBerla makes use of these iterator macros. Actually, there are a lot more macros than shown here in this tutorial. They are useful even when iterating only parts of a field. For documentation of all available macros, please have a look here: Field Iterator Macros.

The current implementation still has a performance issue: In every time step, memory for a complete field has to be allocated, the field values have to be copied and finally the copy has to be destroyed again. For real-life sweeps, one usually has two fields: a source and a destination field. One is used for writing the other for reading. After the sweep the two fields are swapped. Swapping is a fast operation since internally only the pointer to the data of the Field classes are swapped.

The most interesting aspect of the Game Of Life is the initial configuration. Since we effectively have a two-dimensional domain, we initialize our fields using a gray scale png image. First, we load the image using the geometry::GrayScaleImage. Depending on the size of the image, we create the BlockStorage:

After that, we use a initializer class from the geometry module to initialize the fields using the gray scale values of the image:

For a detailed description, have a look at geometry::initializer::ScalarFieldFromGrayScaleImage.

There is also a mechanism available to read the geometry information from a configuration file: The relevant classes are all in the geometry::initializer namespace, which can be registered at a geometry::initializer::InitializationManager. The latter handles the reading of the configuration file.